![]() This article first appeared in TW,

the magazine of St John's College,

Oxford, and is reproduced by kind permission of the Editor.

This article first appeared in TW,

the magazine of St John's College,

Oxford, and is reproduced by kind permission of the Editor.

The maps were drawn by Ailsa Allen, Senior Cartographer in the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford.

![]() 'A summary of the project'

'A summary of the project'

![]() 'How many forests survived into and through early modern times?'

'How many forests survived into and through early modern times?'

A map of Bringewood Chase and Mocktree Forest in 1662 (Herefordshire County Record Office, T87/1. Reproduced by kind permission of the holders).

he

growth of environmental concerns and studies, a more intense awareness of

the fragility of the relationship between humankind and the nature we have

to a large degree created, or perilously altered, have combined to give

geography a new centrality and interest for undergraduates. Jack Langton,

our Fellow in Geography, is embarking on a far-reaching research project

which will show how legal and political interference in English forests

was well under way many centuries before the first logger had set foot in

the Amazon. Yet the stor y of this interference is far more complex than

the slash-and-burn policies of contemporar y rain-forests. The equivocal

status of the English forests enabled them to flourish as centres of

resistance towards modernity, sequestered places in which significant

political, religious, and social counter-cultures flourished, protected

from contemporary eyes and consequently only to be restored to our gaze by

careful research.

he

growth of environmental concerns and studies, a more intense awareness of

the fragility of the relationship between humankind and the nature we have

to a large degree created, or perilously altered, have combined to give

geography a new centrality and interest for undergraduates. Jack Langton,

our Fellow in Geography, is embarking on a far-reaching research project

which will show how legal and political interference in English forests

was well under way many centuries before the first logger had set foot in

the Amazon. Yet the stor y of this interference is far more complex than

the slash-and-burn policies of contemporar y rain-forests. The equivocal

status of the English forests enabled them to flourish as centres of

resistance towards modernity, sequestered places in which significant

political, religious, and social counter-cultures flourished, protected

from contemporary eyes and consequently only to be restored to our gaze by

careful research.

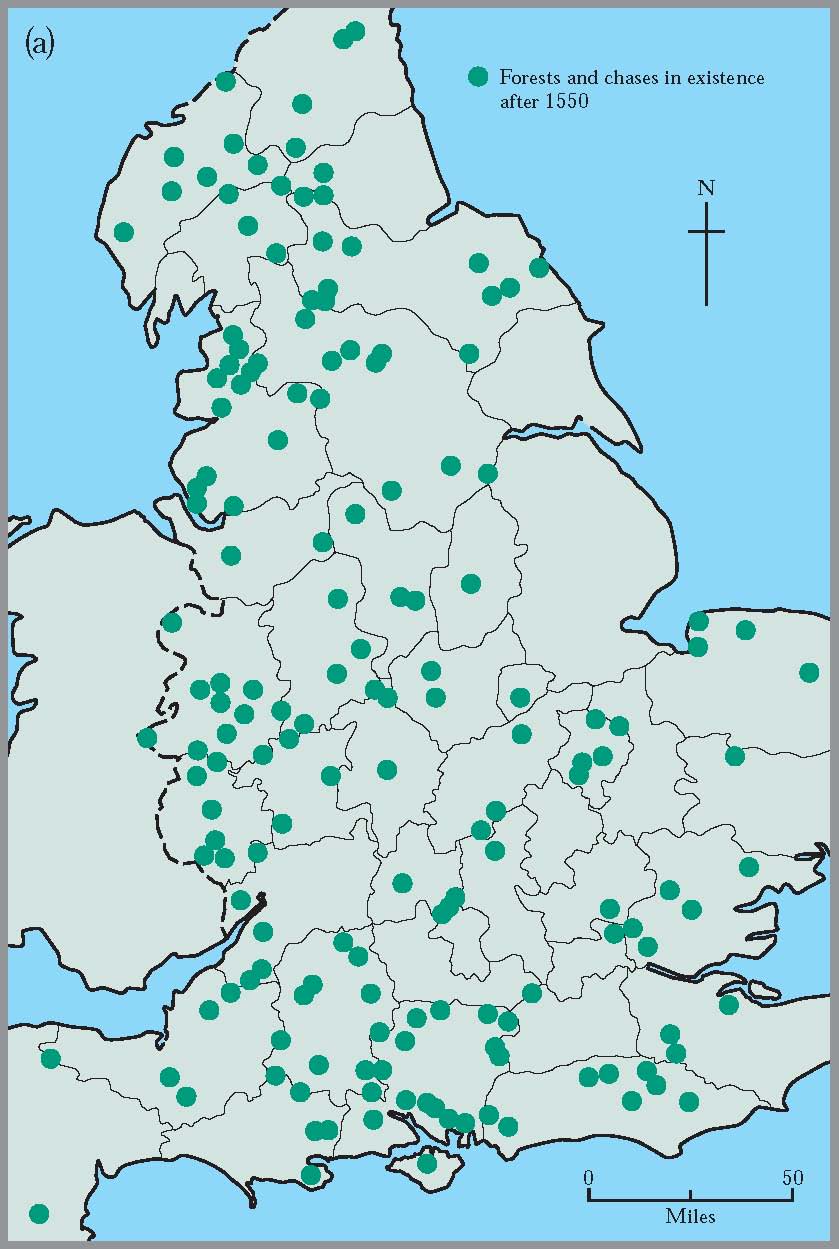

(a) Forests and chases in the late sixteenth century.

or a pasture” (that is, other grounds suited to hunting), which might belong to subjects. Everything appeared to be neat and tidy: ‘forests’ must be ‘Royal’, and therefore under the jurisdiction of the Forest Eyres, through which Forest Law was administered to facilitate the king’s hunting, and who purchased their rights to fines and favours from Chief Justices in Eyre for the Forests (an office which was not abolished until 1828).

In fact, despite these functionaries (and the festoon of other officers they supported), the situation was far less straightforward than the lawyers represented.

Surveyors sent to reveal the extent and contents of the now unequivocally categorised forests found shocking neglect. John Norden reported in 1615 that “time and discontinuance of use have forgotten the names, altered the bounds and lost the lands formerly known, used and enjoyed as belonging unto his Majesty’s Chase of Fillwood”. All the ‘desert forests’ contained “idleness, beggary and atheism . . . wherein infinite poor, yet most idle inhabitants have thrust themselves, living covertly without law or religion . . . among whom are nourished and bred infinite idle fry, that coming to ripe grow vagabonds and infect the commonwealth with a most dangerous leprosy”.

No wonder forests have been neglected in favour of celebrating or lamenting what their extinction enabled. Most mentions of them in early modern times relate to trees, and many were disfranchised and sold. But a large number were not, and because disfranchisement left vast commons and hunting parks, legally defunct forests had long after-lives across centuries of irresolvable claims by sub-franchisees, officers and commoners.

Forests survived because they remained indispensable to the crown and aristocracy for deer hunting and patronage through granting perquisite-laden offices, invitations and licences to hunt, and presents of venison (which could not legally be bought and sold until 1827). Forests and forest lordship were symbols of supreme privilege. Vanburgh’s three most sumptuous palaces were in or neighboured forests, where the authority of sheriffs and justices of the peace did not run; no borough or market charters could be granted; all through-traffic must pay fines when deer were fawning, and resident landowners, however illustrious, owed medieval obeisance to forest lords. Before the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts in 1829, Roman Catholic peers and nouveaux très riches, who were excluded from the political establishment, were particularly appreciative of the authority, seclusion and diversion of forests, and the freedom from church intrusion entailed by their extra-parochiality.

(b) Forests and chases in central southern England in the late sixteenth century.

Absent or confused jurisdictions also benefited other forest dwellers, who were as numerous as common wastes were extensive. They shared the aristocracy’s cornucopia of deer, game and wood, and freedom for cultural defence and manoeuvre. According to Anne Barton, Shakespeare was “haunted . . . by the ghost of the forest of Arden”, and Christopher Hill noted “that the early Quaker movement was especially successful in attracting converts in forest, woodland and fen areas”.

In fact, there was a close geographical coincidence between forests, witchcraft and religious ebullience of all sorts. Demdike, a notorious witch who died in 1612, lived in Pendle Forest. A century earlier Mother Shipton practised the black arts in Knaresborough Forest. McCulloch stressed that William Tyndale “was from that independently-minded and fiercely self-contained home of Lollards, the forest of Dean”. In 1739 Wesley’s first English field preachings were in Kingswood Forest.

Most places where ordinary people used the courts to defend customary common rights (which were also being textually specified in order to destroy them) happen also to have been in forests. When this failed the “most dangerous leprosy” broke out. Over half the Northamptonshire rioters in The Midlands Revolt of 1607 came from Rockingham Forest. In the 1630s most incidents of The Western Rising occurred in forests and there were riots in at least ten elsewhere.

After 1660 the customs of the “infinite idle fry” were continually made more severely criminal by new laws protecting deer, game and trees. Forests contained the bloodiest battlefields of the subsequent poaching war that shattered rural society. The seditious proclamation of 1812 was issued from “Ned Lud’s Office, Sherwood Forest”. Forests provided hugely disproportionate numbers of Captain Swing rioters in 1830-31. The last rising of the agricultural labourers erupted from Dunkirk Forest in 1838.

Far from subsiding into timely disappearance, forests survived as recalcitrant spaces, resistant to modernisation of all kinds. If recent historians of English culture are right, a fully-fledged counterculture flourished in the forests. Outside modernity’s terms of reference, opaque to its scrutiny and resistant to its imperatives, forests were arenas for activities otherwise linked only by irrelevance to capitalism, improvement, conformity and propriety.

The reasons why it survived make it impossible to discover the full extent of this other England; that is, the wide discrepancy between textual representations and what they purported to categorise. Even the primary term ‘royal forest’ dissolves when its components are examined. ‘Royal’ properties excluded the estates of the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall and of queen consorts and dowagers, which contained many forests. So did palatinates and marcher lordships. Maybe in pettifoggery these were really ‘chases’. The reality of non-royal forests was acknowledged in 1817 when Parliament gave the Duchy of Lancaster the right “to sell rights of forest, free chase and free warren over lands of individuals to the owners of these lands, in order to extinguish” them.

Like the chases and warrens of the Crown, royal duchies and consorts, they had, in fact, been administered as ‘royal forests’. From Henry VIII onwards this was done through other courts than Forest Eyres, of which few were summoned after the fourteenth century. Aristocrats did the same. Lord Rivers was assured in the 1820s that his rights under medieval Forest Law, which were assiduously enforced, had not been curtailed by other legislation.

To discover the forests we must get behind ‘royal forest’ and other simplifying abstractions. In doing so we re-encounter the contradictions and inconsistencies that those legal figments were intended to resolve: little overlap between successive itemisations (see illustration); particular forests with different names, and different ones with the same name; parts of forests denoted as separate ones; franchises of forest, chase, park or warren in crown and subjects’ hands; forests alternating as chases and warrens and boundaries that are hard to locate on today’s maps.

Our second illustration shows something of what has been recovered from groping between textual categories and the reality they misrepresented. Huge areas lay within three times more forests and chases (let alone warrens) than the royal forests. Further retrieval, eventually to produce an atlas, needs a lot more work in archives throughout England. Many of the primary sources are large plans of the kind partly illustrated on our third illustration, and specialist expertise is required to capture and digitally manipulate them. Thanks to a grant of reduced teaching duties, I anticipate many happy hours in the College’s Research Centre.